April 22, 2013 - By Tracie White

Alternative spring-breakers Mason Alford, Arhana Chattopadhyay, Melanie Langa and Margreth Mpossi at the Rosebud Sioux Reservation hospital in South Dakota.Arhana Chattopadhyay was on an emotional high. The first-year Stanford medical student had just seen a baby born for the first time, and was able to assist in the cesarean section by comforting the mother during surgery. She had completed her first pelvic exam, on a young woman with severe abdominal pain, and helped conduct a CT scan on an intoxicated assault victim with a bloody gash on his head.

In a single day working as a medical volunteer in the second-poorest county in the United States — where life expectancy for men is 47, lower than it is in Haiti, and an overburdened staff and underfunded hospital daily face epidemic levels of alcoholism, diabetes and suicide — Chattopadhyay had experienced firsthand the thrill of making a difference.

"It was awesome. It was incredible. I was standing at the head of the operating table, having a conversation with the mother, who had received an epidural. I could see the obstetrician moving aside her uterus," she said, glowing with excitement when she returned to the emergency room staff office at the 36-bed Rosebud Indian Health Service Hospital, where she and several Stanford students were stationed for the day. "I got to do so much. The doctors really loved teaching us."

Chattopadhyay was one of 14 Stanford medical and undergraduate students who flew into Sioux Falls, S.D., then drove four hours west to the Rosebud Sioux Reservation, a community with one traffic light, located in the middle of the state's windswept plains, where the nearest laudromat is an hour's drive.

The students and instructors visit Mount Rushmore, in the western part of South Dakota.

The weeklong trip in March was the conclusion of a medical school course titled "Alternative Spring Break: Rural and American Indian Health Disparities." The student-generated class, now in its fifth year, was designed to expose students to the social injustices and historical context that have helped contribute to the heavy disease burden of the Rosebud Lakota Sioux and other Native Americans. The course also introduced the students to possible careers in rural medicine and a proud community struggling to keep Lakota traditions alive.

"One week can't fix things," said Adrian Begaye, who along with fellow third-year Stanford medical student Keith Glover instructed this year's course and led the trip. Both men are tribal members of the Navajo Nation. "But we can come to a greater understanding of the needs of underserved populations and influence the course of some students' careers," Begaye added.

Staying in the Habitat for Humanity dorms in Mission, a community on the reservation, the 12 students in the class — only one of them, Layton Lamsam, was American Indian — and Begaye and Glover spent their days alternating between helping to build houses for the reservation, where poorly heated trailers are the norm, and volunteering at the hospital. The medical students were able to assist doctors while the undergraduates shadowed hospital staff.

In the evenings, the students met with community leaders who taught them about such problems as the inaccessibility of nutritional food due to geographic isolation, and poor education due to difficulties recruiting teachers. Youth leader Shane Red Hawk discussed the levels of hopelessness that have led the community to be ranked among those with the highest suicide rates in the world.

The Rosebud Sioux Reservation, on the plains of South Dakota, is not your typical destination for spring break, but it's where 14 Stanford students, including seven medical students, spent theirs last month.

"There is a lot of hopelessness and despair," said Red Hawk, who along with his wife, Noella, runs the Buffalo Jump youth center and restaurant in Mission, where the class met for a dinner of fry bread tacos. "I've had kids brought to me after being cut down from trying to hang themselves," he said. "It's humbling when a teenager arrives with swollen lips, and fingers still blue."

Students traveled to the Rosebud Reservation with a basic scholastic understanding of the health-care problems facing the community and some of the tragic history of the Sioux. They had learned from lectures and readings of the federal government's obligation to provide health care free of charge to Native Americans as a result of treaties signed in exchange for land. They also learned that the Indian Health Service, part of the Department of Health and Human Services, assigned to provide health care to 2 million Native Americans and Alaskan Natives, is notoriously underfunded. The U.S. Commission on Civil Rights found the federal government spends about $5,000 per capita each year on health care for the general U.S. population, $3,803 on federal prisoners and $1,914 per capita on Indian health care.

On the reservation, the students experienced what this means in human terms.

"We're looking for quarters under seat cushions," said Ira Salom, MD, chief medical officer recruited to the hospital from New York City. "It's hard recruiting here. We're always underfunded and understaffed."

Each morning, students sat in on the hospital meetings, hearing firsthand the daily struggles of the staff. They heard about the pregnant patient with diabetes who lost her baby the night before, her wails echoing down the hospital halls; they heard about yet another suicide victim, a 25-year-old man who hanged himself two days before. They listened to the staff triaging what levels of care they could afford to provide.

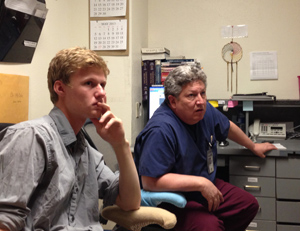

Alford and physician assistant Rick Emery wait for an ambulance to arrive with men injured in a fight.

"We're fragile here. We don't have a deep bench," said Salom, after hearing that they were short a medical technician, who was out sick that day, meaning the CT machine would be down, and that there was no night staff available for the first week of April in the emergency room.

But students also heard the positive side of a career in rural health, in which physicians provide "holistic care" to their patients whom they come to know well and see around the small community — at the post office, at powwows and in schools.

"It's a very rewarding place to work," said Douglas Lehmann, MD, an Illinois native and family practice physician who has partnered with the Stanford class since it started five years ago. "If you want to make a difference, this is a place for you. It's a challenge working in the government system with limited funds. You get crafty. You learn to fix things with a roll of duct tape."

You also learn how to treat impoverished patients who are in desperate need of a good physician, one who will listen and provide good care, he said. "The most important question I ask is, 'How are you doing today?' If your daughter has just been put in jail or just died in an alcohol-related accident, it affects health. 'Do you have a car? How many kids do you have?' These are the important questions. You do a lot more than most doctors. I get a lot more satisfaction here."

Nearing the end of the week, while cooking bison fajitas in their dorm kitchen, the students found time to discuss their experiences in the hospital — the good and the bad, the tragic and the heroic.

"It opened my eyes," said Roxana Daneshjou, an MD/PhD student. "I don't think I had a very good understanding of what living on a reservation was like. It was shocking. Just seeing a health-care-delivery system not working. We are not taking care of our people."

Daneshjou talked about the patient she helped treat who had returned to the hospital after suffering a severe fracture in her arm two months ago. Due to the lack of orthopaedic care, she was back again, her arm still in pain.

"It's just awful. If we were at Stanford, she'd go see a very good orthopaedic surgeon and it would be fine," Daneshjou said. "It's the worst feeling in the world to sit somewhere and know that the ability exists to fix something, and just not see it get done. The doctors were visibly frustrated."

Shaking her head in frustration, she listened to Chattopadhyay, the first-year medical student, who was still excited about helping to birth her first baby that day.

"At times, they don't have a general surgeon, often the OB doesn't even have an assistant. I can't even imagine it," Chattopadhyay said. Then, her eyes lighting up, she added, "But I saw patients getting very good care even with the lack of resources. The doctors were amazing."

Gabriel Garcia, MD, professor of medicine and faculty adviser to the course, said that he hopes the course will continue, eventually forging a long-term relationship with the Rosebud Reservation, because the learning opportunities for students are incalculable and because he believes one week on the Rosebud Reservation can make a difference.

"The question often arises, what can you do in just one week?" said Krishnan Subrahmanian, MD, a graduate of the School of Medicine, who co-founded the course with fourth-year Stanford medical student Shane Morrison. The two first took students to the reservation, where Subrahmanian had worked for two years as a teacher. "A week can start a month can start a year can start a lifetime of work. This may change what your future will be."

About Stanford Medicine

Stanford Medicine is an integrated academic health system comprising the Stanford School of Medicine and adult and pediatric health care delivery systems. Together, they harness the full potential of biomedicine through collaborative research, education and clinical care for patients. For more information, please visit med.stanford.edu.