February 24, 2009 - By Krista Conger

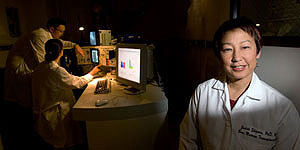

Credit: Steve Fisch Photography

Judith Shizuru and colleagues showed that when purified blood stem cells are used in marrow transplants in mice, it reduces the risk of graft-versus-host disease.

Purified blood stem cells may be a better alternative to mixtures of cells for the bone marrow transplants typically done to treat leukemia and lymphoma, said researchers at the School of Medicine.

The finding belies conventional wisdom, which holds that some mature immune cells from the donor are necessary to protect the patient, who is the recipient, from infections that can occur immediately after transplant. Instead, said the researchers, using stem cells alone avoids clinically undetectable levels of the graft-versus-host disease that can degrade the procedure's success.

The research, from the lab of hematologist Judith Shizuru, MD, PhD, was published online Feb. 16 in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

Blood stem cells, which reside in the bone marrow, can generate every type of blood and immune cell. They are the only cells necessary to re-establish blood formation in patients treated with lethal doses of cancer-eradicating radiation or chemotherapy. However, studies have shown that patients treated with partially enriched blood stem cells - that is, bone marrow that had been treated to remove most of the supposedly unnecessary mature immune cells also found in the marrow - were significantly more susceptible to infectious complications after transplant than were those who had received whole, untreated bone marrow. Clinicians thought that this might be because it took too long to generate mature, functional immune cells from the transplanted stem cells.

As a result, the standard of care now involves transplanting either bone marrow or blood in which the proportion of circulating stem cells has been artificially enhanced, but it does not involve purified stem cells. Rather, the patient receives a combination of stem cells and functioning immune cells that are supposed to provide immediate protection against infections. The problem is that these mature donor cells can also turn against the patient and attack surrounding tissue they perceive as foreign.

So clinicians walk a thin line between protecting their transplant patients from infection and preventing this 'graft-versus-host' disease, or GVHD. To reduce the chance of GVHD, doctors try to find a donor who is immunologically similar to the transplant patient.

Shizuru, associate professor of medicine, and her colleagues, including otolaryngology resident Gabriel Tsao, MD, and graduate student Jessica Allen, transplanted either bone marrow or purified blood stem cells into three increasingly diverse combinations of laboratory mice. They found that, regardless of the degree of diversity between the host and the donor, the lymph nodes of mice who received the purified stem cells were larger and healthier-looking than those of mice that had received transplants of whole bone marrow. The recipients of the purified cells also responded more robustly when challenged with a foreign peptide, or small protein. Together these findings suggest that mice that received the whole bone marrow were suffering from low levels of GVHD that impacted their ability to recover after transplant.

Based on the mouse experiments, the researchers inferred that partially enriching for blood stem cells is likely not sufficient to prevent GVHD in human patients and that even sub-clinical GVHD damages the immune system. Translating these principles from mice to people - and transplanting purified blood stem cells into human patients - may one day yield more effective, safer transplants, they said.

About Stanford Medicine

Stanford Medicine is an integrated academic health system comprising the Stanford School of Medicine and adult and pediatric health care delivery systems. Together, they harness the full potential of biomedicine through collaborative research, education and clinical care for patients. For more information, please visit med.stanford.edu.