October 4, 2006

He and his father are the sixth father and son to win Nobel Prizes

STANFORD, Calif. — The Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences today awarded Roger Kornberg, PhD, of the Stanford University School of Medicine, the 2006 Nobel Prize in Chemistry for his work in understanding how DNA is converted into RNA, a process known as transcription.

In 2001 Kornberg published the first molecular snapshot of the protein machinery responsible — RNA polymerase — in action. The finding helped explain how cells express all the information in the human genome, and how that expression sometimes goes awry, leading to cancer, birth defects and other disorders.

“I’m simply stunned. There are no other words,” said Kornberg, a professor of structural biology, this morning after the 2:30 a.m. call. “It’s such astonishing news.” The scene at Kornberg’s house was one of controlled chaos, with nonstop telephone calls from well wishers and media.

Roger Kornberg

Kornberg, who is also the Mrs. George A. Winzer Professor in Medicine, is the School of Medicine's second Nobel Prize winner this week. On Monday, Andrew Fire, PhD, professor of pathology and of genetics, was a winner of the 2006 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine for his work on RNA interference. Together the two awards serve as a clarion announcement of RNA’s arrival in the scientific and medical spotlight.

“Roger has been one of my role models for many years,” said Fire. “We did our post-docs at Cambridge in the same institute, and he’s been a tremendous help to me since I came to Stanford in 2003. Our fields are interestingly intertwined.”

Kornberg’s research, and latest award, is a family affair: his father Arthur Kornberg, PhD, was awarded the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 1959 for studies of how genetic information is transferred from one DNA molecule to another. The Kornbergs are the sixth father-son team to win Nobel Prizes, in addition to one father-daughter team.

“I have felt for some time that he richly deserved it,” said the elder Kornberg after hearing about his son’s award. “His work has been awesome.” Arthur Kornberg is the Emma Pfeiffer Merner Professor of Biochemistry, Emeritus, at the School of Medicine. He learned of the award from a nephew in LaJolla, Calif., who had been called accidentally by someone looking for Roger.

“Roger Kornberg is one of our nation’s treasured scientists,” said Philip Pizzo, MD, dean of the School of Medicine. “He has dedicated his life and career to using the powerful tools of structural biology to elucidate the molecular mechanism of transcription. His remarkable studies have been acclaimed for their elegance and technical sophistication as well as the unique insights they have yielded. His work has deepened our understanding of the ‘message of life’ and how it contributes to both normal and abnormal human development, health and disease.”

Kornberg emphasized that the work required many contributions. “I am indebted to my colleagues,” he said. “This is not something that I did alone, or even with a small number of people. It is the result of the hard work, insight and inspiration of very many exceptionally talented Stanford students and post-docs.”

Selective transcription of a cell’s tens of thousands of genes determines whether it becomes a neuron, a liver cell or a stem cell — and whether it develops normally or becomes a runaway cancer. The picture of RNA polymerase at work provided an atomic-level window into how the protein complex unzips and then re-zips the double-stranded DNA like a Ziploc bag after using the internal code to build a specific RNA molecule. It was a thing of beauty for biologists around the world.

“We were astonished by the intricacy of the complex, the elegance of the architecture, and the way that such an extraordinary machine evolved to accomplish these important purpose,” said Kornberg of the images he and his colleagues created. “RNA polymerase gives a voice to genetic information that, on its own, is silent.” Learning how that voice is amplified — and shushed — through the selective expression of genes is a critical stepping stone to many areas of biological and medical research.

The path to the pictures involved a highly specialized field at the intersection of chemistry, biology and physics called crystallography. The technique, as much art as science, is the same one used by Francis Crick, Rosalind Franklin and James Watson to determine the double-stranded nature of DNA. In general, it involves evaporating a concentrated solution of a molecule until all that’s left are highly structured crystals somewhat like the crust of salt left behind by drying seawater. Extremely bright X-rays are then able to pinpoint the position of individual atoms and the data are used to produce a computer-generated representation of the molecule.

The transcription process visualized by Roger Kornberg and his colleagues in his X-ray crystallography studies published online April 19, 2001, in Science. The protein chain shown in grey is RNA polymerase, with the portion that clamps on the DNA shaded in yellow. The DNA helix being unwound and transcribed by RNA polymerase is shown in green and blue, and the growing RNA stand is shown in red

Successfully crystallizing one molecule is a feat worth congratulating. Capturing the 10 subunits of RNA polymerase in action on the DNA was unthinkable.

“It was a technical tour de force that took about 20 years of work to accomplish,” said Joseph Puglisi, PhD, professor and chair of the department of structural biology at the School of Medicine. “Like other great scientists, Roger doesn’t quit. He’s stubborn. A lot of scientists would have given up after five years.” Kornberg’s determination, coupled with his expertise in both crystallography and biochemistry, finally cracked the code.

“I'm a biochemist and he’s a biochemist, but beyond that he’s a crystallographer, a structural chemist and a geneticist,” said Arthur Kornberg. Roger Kornberg devised a way to first initiate the process of transcription in a test tube and then stall it by withholding one of the building blocks of RNA. Crystallizing the frozen complex showed the relative positions of the polymerase, the DNA template and the growing RNA strand.

“Professor Kornberg’s seminal research on transcription has been an exceptional contribution to the body of knowledge in fundamental biology,” said Stanford University President John Hennessy. “His work settled long-open questions about how genes communicate the information needed to make proteins and will help us understand a variety of diseases that can be caused by a failure in the transcription process. For the second time this week, a colleague’s achievement reminds us of the unique role universities have in advancing basic knowledge. We are proud to claim Professor Kornberg and his father Arthur as members of the Stanford family. I offer Roger warm congratulations on behalf of the entire university community.”

Prior to beginning his work studying the molecular mechanism of transcription, Kornberg discovered the nucleosome, the basic unit from which all chromosomes are made. In 1974, as a junior scientist at Cambridge University, he proposed that the massive amounts of DNA contained in every cell could be compactly stored by wrapping it in its condensed form—the chromosome—around eight histone protein “spools” to form nucleosome “beads.” Kornberg and his wife and collaborator Yahli Lorch, PhD, associate professor of structural biology at Stanford, were instrumental in identifying the nucleosome as fundamental to transcription. Since then, it has been recognized that disruptions involving the nucleosome underlie many cancers and other diseases.

Born in 1947, Kornberg was the first of three children born to Arthur Kornberg and his wife, Sylvy, who was also a biochemist working with Arthur

“Roger was a scientist from the beginning; He never showed any other interest,” said his brother, Thomas Kornberg, PhD, a professor of biochemistry at the University of California-San Francisco.

“Both my parents had fine scientific minds and taught by example how to approach questions and problems in a logical, dispassionate way,” Roger Kornberg once said. “Science was a part of dinner conversation and an activity in the afternoons and on weekends. Scientific reasoning became second nature. Above all, the joy of science became evident to my brothers and me.” Kornberg was able to indulge his scientific bent early as a high school student working in the laboratory of Paul Berg, a colleague of his father’s at Stanford who won the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 1980.

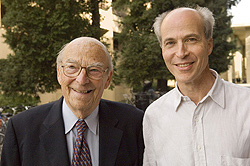

Arthur and Roger Kornberg

The senior Kornberg said his son’s winning did not come entirely out of the blue. He had mentioned the chemistry prize yesterday in a conversation with his son, who had just returned from a trip to Jerusalem. “I talked to him at length and couldn’t help but discuss this possibility — I know he’s been shortlisted in previous years,” said the elder Kornberg. “He dismissed it, saying it was a possibility but he didn’t expect it, but that’s the way it goes.”

Arthur Kornberg said he had not imagined decades ago, when his son first began his career as a biochemist, that there would be a second Nobel laureate in the family. “Of course not,” he remarked. “But nature is so broad, profound and mysterious — one doesn’t know where it leads. And I would say among the people I know — and I have trained many hundreds — he has the clearest vision, sense of purpose and direction.”

Pizzo paid tribute to the contributions of both father and son to Stanford. “Arthur Kornberg played a major role in transforming the Stanford University School of Medicine into a research-intensive powerhouse,” Pizzo said. “He was clearly productive in both his professional life and his private life—since he is the father of remarkably talented children, including Roger—who has sustained a legacy of brilliance and commitment to science and the deepening of our understanding of human life.”

Roger Kornberg received his undergraduate degree in chemistry from Harvard in 1967 and his doctorate in chemistry from Stanford in 1972, studying the motion of lipids in cell membranes. He was a postdoctoral fellow and member of the scientific staff at the Laboratory of Molecular Biology in Cambridge, U.K., from 1972 to 1975. He joined Harvard Medical School in 1976 as an assistant professor in biological chemistry. Kornberg returned to Stanford in 1978 as a professor in structural biology. He served as department chair from 1984 until 1992.

Kornberg is an elected member of the National Academy of Sciences and of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences, and an honorary member of the Japanese Biochemical Society. He is editor of the Annual Reviews of Biochemistry. He has written more than 180 peer-reviewed journal articles.

His previous honors and awards include the Eli Lilly Award (1981), the Passano Award (1982), the Harvey Prize (1997), the Gairdner International Award (shared in 2000 with Robert Roeder), the Welch Award (2001) and the Grand Prix of the French Academy of Sciences (2002).

“One of the benefits of the recognition of work such as ours is that it encourages continued support of fundamental issues like this one,” said Kornberg. “Many of the major advances in human health have their origins in the pursuit of basic biological knowledge.”

His funding sources agree. “Through decades of elegant, state-of-the art studies in biochemistry and structural biology, Roger Kornberg has revealed the mechanism underlying how cells transcribe genetic information," said Jeremy M. Berg, PhD, director of the National Institute of General Medical Sciences, which has funded Kornberg’s research since 1979. “This knowledge sheds light on a fundamental process that is key to health and disease. The achievement also demonstrates the power of innovative approaches to probe the many complicated molecular assemblies essential to life.”

Despite the kudos, wining such a prestigious award can create complications: Kornberg was scheduled to fly to Pittsburgh tonight to receive the Dickson Prize in Medicine. When he called this morning to cancel his flight, the Travelocity operator wanted to know the reason. There was a pause, and a gulp.

“Well,” he said. “I just won the Nobel Prize in Chemistry.” There’s no word yet as to the operator’s response, but perhaps he can roll the ticket over to his upcoming trip to Sweden.

“I'm looking forward to being in Stockholm, where we have many friends,” said Arthur Kornberg, remembering his own award 47 years ago. “They put on a great party.”

About Stanford Medicine

Stanford Medicine is an integrated academic health system comprising the Stanford School of Medicine and adult and pediatric health care delivery systems. Together, they harness the full potential of biomedicine through collaborative research, education and clinical care for patients. For more information, please visit med.stanford.edu.