Division News

Excerpts from the Stanford medical community

Antibodies in blood soon after COVID-19 onset may predict severity

A look at antibodies in patients soon after they were infected with the virus that causes COVID-19 showed key differences between those whose cases remained mild and those who later developed severe symptoms.

January 18, 2022 - By Bruce Goldman

Blood drawn from patients shortly after they were infected with SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19, may indicate who is most likely to land in the hospital, a study led by Stanford Medicine investigators has found.

“We’ve identified an early biomarker of risk for progression to severe symptoms,” said Taia Wang, MD, PhD, assistant professor of infectious diseases and of microbiology and immunology. “And we found that antibodies elicited by an mRNA vaccine — in this case, Pfizer’s — differ in important, beneficial ways from those in people infected with SARS-CoV-2 who later progress to severe symptoms.” The upshot could eventually be a test that, given soon after a positive COVID-19 result, would help clinicians focus attention on those likely to need it most.

More

A paper describing the study’s findings was published Jan. 18 in Science Translational Medicine. Wang shares senior authorship with Gene Tan, PhD, assistant professor at the J. Craig Venter Institute in La Jolla, California. Lead co-authors of the study are Stanford postdoctoral scholar Saborni Chakraborty, PhD, and graduate student Joseph Gonzalez.

“Severe COVID-19 is largely a hyperinflammatory disease, particularly in the lungs,” Wang said. “We wondered why a minority of people develop this excessive inflammatory response, when most people don’t.”

To find out, Wang and her colleagues collected blood samples from 178 adults who had tested positive for COVID-19 upon visiting a Stanford Health Care hospital or clinic. At the time of testing, these individuals’ symptoms were universally mild. As time passed, 15 participants developed symptoms bad enough to land them in the emergency department.

Taia Wang

Antibodies show distinctions

Analyzing the antibodies in blood samples taken from study participants on the day of their coronavirus test and 28 days later, the researchers ferreted out some notable differences between those who developed severe symptoms and those who didn’t.

Antibodies are proteins shaped, roughly speaking, like two-branched trees. They’re produced by immune cells and secreted in response to things the body perceives as foreign, such as microbial pathogens. An amazing feature of antibodies is that their branches can assume a multitude of shapes. The resulting spatial and electrochemical diversity of the areas defined by antibodies’ branches and their intersection is so great that, in the aggregate, antibodies take on all comers.

When an antibody’s shape and electrochemistry is complementary to a feature of a pathogen, it gloms on tightly. Sometimes the adherence isn’t in the right spot to prevent the pathogen from doing its nefarious business. Antibodies that bind pathogens in just the right places, preventing infection, are called neutralizing antibodies.

In either case, the resulting adhesion generates what’s called an immune complex, drawing immune cells to the site.

The researchers found that while many participants whose symptoms remained mild had healthy levels of neutralizing antibodies to SARS-CoV-2 from the get-go, participants who wound up hospitalized had initially minimal or undetectable levels of neutralizing antibodies, although their immune cells started pumping them out later in the infection’s course.

A second finding involved an often-neglected structural aspect of antibodies’ “trunks”: They are decorated with chains of various kinds of sugar molecules linked together. The makeup of these sugar chains has an effect on how inflammatory an immune complex will be.

We wondered why a minority of people develop this excessive inflammatory response, when most people don’t.

Many types of immune cells have receptors for this sugar-coated antibody trunk. These receptors distinguish among antibodies’ sugar molecules, helping to determine how fiercely the immune cells respond. A key finding of the new study was that in participants who progressed to severe COVID-19, sugar chains on certain antibodies targeting SARS-CoV2 were deficient in a variety of sugar called fucose. This deficiency was evident on the day these “progressors” first tested positive. So, it wasn’t a result of severe infection but preceded it.

Furthermore, immune cells in these patients featured inordinately high levels of receptors for these fucose-lacking types of antibodies. Such receptors, called CD16a, are known to boost immune cells’ inflammatory activity.

“Some inflammation is absolutely necessary to an effective immune response,” Wang said. “But too much can cause trouble, as in the massive inflammation we see in the lungs of people whose immune systems have failed to block SARS-CoV-2 quickly upon getting infected” — for example, because their early immune response didn’t generate enough neutralizing antibodies to the virus.

A look at vaccine response

The scientists also studied the antibodies elicited in 29 adults after they received the first and second doses of the Pfizer mRNA vaccine. They compared these antibodies with those of adults who didn’t progress to severe disease about a month after either being vaccinated or infected; they also compared them with antibodies from individuals hospitalized with COVID-19. Two vaccine doses led to overall high neutralizing-antibody levels. In addition, antibody fucose content was high in the vaccinated and mildly symptomatic groups but low in the hospitalized individuals.

Wang and her associates tested their findings in mice that had been bioengineered so their immune cells featured human receptors for antibodies on their surfaces. They applied immune complexes — extracted, variously, from patients with high levels of fucose-deficient antibodies, patients with normal levels or vaccinated adults — to the mice’s windpipes. The investigators observed four hours later that the fucose-deficient immune-complex extracts generated a massive inflammatory reaction in the mice’s lungs. Neither normal-fucose extracts nor extracts from vaccinated individuals had this effect.

When the experiment was repeated in similar mice that had been bioengineered to lack CD16a, there was no such hyperinflammatory response in their lungs.

Wang said the immunological factors the researchers have identified — a sluggish neutralizing-antibody response, deficient fucose levels on antibody-attached sugar chains, and hyperabundant receptors for fucose-deficient antibodies — were each, on their own, modestly predictive of COVID-19 severity. But taken together, they allowed the scientists to guess the disease’s course with an accuracy of about 80%.

Wang speculates that the abundance of CD16a on immune cells and the relative absence of fucose on antibodies’ sugar chains may not be entirely unrelated phenomena in some people, and that while neither alone is enough to consistently induce severe inflammatory symptoms following SARS-CoV-2 infection, the combination leads to a devastating inflammatory overdrive.

Other Stanford co-authors of the study are postdoctoral scholars Vamsee Mallajosyula, PhD, Megha Dubey, PhD, Usama Ashraf, PhD, Bowie Cheng, PhD, Nimish Kathale, PhD, Fei Gao, PhD, and Prabhu Arunachalam, PhD; life science research professionals Kim Tran and Courtney Scallan; genomics manager Xuhuai Ji, MD, PhD; Scott Boyd, MD, PhD, associate professor of pathology; Mark Davis, PhD, director of the Stanford Institute for Immunity, Transplantation and Infection and professor of microbiology and immunology; Marisa Holubar, MD, clinical associate professor of infectious diseases; Chaitan Khosla, PhD, professor of chemical engineering and of chemistry; Holden Maecker, PhD, professor of microbiology and immunology; Yvonne Maldonado, MD, professor of pediatric infectious diseases and of epidemiology and population health; Elizabeth Mellins, MD, professor of pediatric human gene therapy; Kari Nadeau, MD, PhD, professor of medicine and of pediatrics; Bali Pulendran, PhD, professor of pathology and of microbiology and immunology; Upinder Singh, MD, professor of infectious diseases and geographic medicine and of microbiology and immunology; Aruna Subramanian, MD, clinical professor of infectious diseases; PJ Utz, MD, professor of immunology and rheumatology; and Prasanna Jagannathan, MD, assistant professor of infectious diseases and of microbiology and immunology.

Researchers from San Jose State University; the University of California, San Francisco; the Icahn School of Medicine; and Cornell University contributed to the work.

The research was funded by the National Institutes of Health (grants U19AI111825, U54CA260517, R01AI139119, U01AI150741-02S1, 5T32AI007290, U24CA224319 and U01DK124165), Fast Grants, CEND COVID Catalyst Fund, the Crown Foundation, the Sunshine Foundation and the Marino Family Foundation.

Less

Surgical masks reduce COVID-19 spread, large-scale study shows

Researchers found that surgical masks impede the spread of COVID-19 and that just a few, low-cost interventions increase mask-wearing compliance.

September 1, 2021 - By Krista Conger

Providing free masks to people in rural Bangladesh was one measure researchers tested to limit the spread of COVID-19. Courtesy of Innovations for Poverty Action

A large, randomized trial led by researchers at Stanford Medicine and Yale University has found that wearing a surgical face mask over the mouth and nose is an effective way to reduce the occurrence of COVID-19 in community settings.

It also showed that relatively low-cost, targeted interventions to promote mask-wearing can significantly increase the use of face coverings in rural, low-income countries. Based on the results, the interventional model is being scaled up to reach tens of millions of people in Southeast Asia and Latin America over the next few months.

The findings were released Sept. 1 on the Innovations for Poverty Action website, prior to their publication in a scientific journal, because the information is considered of pressing importance for public health as the pandemic worsens in many parts of the world.

“We now have evidence from a randomized, controlled trial that mask promotion increases the use of face coverings and prevents the spread of COVID-19,” said Stephen Luby, MD, professor of medicine at Stanford. “This is the gold standard for evaluating public health interventions. Importantly, this approach was designed be scalable in lower- and middle-income countries struggling to get or distribute vaccines against the virus.”

More

Luby shares senior authorship with Ahmed Mushfiq Mobarak, PhD, professor of economics at Yale, of a paper describing the research. The lead authors are Ashley Styczynski, MD, MPH, an infectious disease fellow at Stanford; Jason Abaluck, PhD, professor of economics at Yale; and Laura Kwong, PhD, a former postdoctoral scholar at Stanford who is now an assistant professor of environmental health sciences at the University of California-Berkeley.

The researchers also partnered with Innovations for Poverty Action, a global research and policy nonprofit organization.

Increasing mask use in rural Bangladesh

The researchers enrolled nearly 350,000 people from 600 villages in rural Bangladesh. Those living in villages randomly assigned to a series of interventions promoting the use of surgical masks were about 11% less likely than those living in control villages to develop COVID-19, which is caused by infection with the SARS-CoV-2 virus, during the eight-week study period. The protective effect increased to nearly 35% for people over 60 years old.

Providing free masks, informing people about the importance of covering both the mouth and nose, reminding people in-person when they were unmasked in public, and role-modeling by community leaders tripled regular mask usage compared with control villages that received no interventions, the researchers found.

In the intervention villages, they also saw a slight increase in physical distancing in public spaces, such as marketplaces. This finding indicates that mask-wearing doesn’t give a false sense of security that leads to risk-taking behaviors — a concern cited by the World Health Organization during the early days of the pandemic when its officials were considering whether to recommend universal masking.

“Our study is the first randomized controlled trial exploring whether facial masking prevents COVID-19 transmission at the community level,” Styczynski said. “It’s notable that even though fewer than 50% of the people in the intervention villages wore masks in public places, we still saw a significant risk reduction in symptomatic COVID-19 in these communities, particularly in elderly, more vulnerable people.”

Cloth vs. surgical masks

There were significantly fewer COVID-19 cases in villages with surgical masks compared with the control villages. (Although there were also fewer COVID-19 cases in villages with cloth masks as compared to control villages, the difference was not statistically significant.) This aligns with lab tests showing that surgical masks have better filtration than cloth masks. However, cloth masks did reduce the overall likelihood of experiencing symptoms of respiratory illness during the study period.

Bangladesh is a densely populated country in South Asia. It was chosen as the site of the trial for several reasons: One, mask promotion is considered vital in countries where physical distancing can be difficult; two, Innovations for Poverty Action Bangladesh had already established a research framework in the country; and three, many local partners were eager to support a randomized, controlled trial of masking.

“We saw an opportunity to better understand the effect of masks, which can be a very important way for people in low-resource areas to protect themselves while they wait for vaccines,” Kwong said. “So we collaborated with behavioral scientists, economists, public health experts and religious figures to design ways to promote mask use at a community level.”

Despite a growing body of scientific evidence that masks reduce the spread of the virus that causes COVID-19, it has been difficult to increase mask-wearing, particularly in low-resource countries and among people living in remote or rural areas. In June of 2020, only one-fifth of Bangladeshis in public areas were wearing a mask that properly covered the mouth and nose despite a nationwide mask mandate that was in effect at the time.

Educational and behavioral interventions

The researchers wanted to explore whether it was possible to increase mask-wearing in Bangladeshi villages through a variety of educational and behavioral interventions over an eight-week study period: Free cloth or washable, reusable surgical masks were given to people at home and in marketplaces, mosques and other public spaces; notable Bangladeshi figures, including the prime minister, a star cricket player and a leading imam, provided information about why wearing a mask is important; people appearing in public places without masks were reminded to wear masks; and community leaders modeled mask-wearing.

The villages were selected by researchers at Innovations for Poverty Action Bangladesh. The researchers paired 600 villages countrywide based on population size and density, geographic location, and any available COVID-19 case data. For each of the 300 pairs of villages, one was randomly assigned to receive the interventions while the other served as a control and received no interventions. Two-thirds of the intervention villages received surgical masks, while the other one-third received cloth masks. In total, 178,288 people were in the intervention group, and 163,838 people were in the control group.

The interventions were rolled out in waves from mid-November to early January. For eight weeks after the interventions, observers stationed at various public places in both the control and intervention villages recorded whether a person was wearing a mask over both their mouth and nose and whether they appeared to be practicing physical distancing — that is, staying at least an arm’s length away from all other people.

At week 5 and week 9, villagers were asked if they had experienced any COVID-19 symptoms — including fever, cough, nasal congestion and sore throat — during the previous month and, if so, whether they would provide a blood sample to test for the presence of SARS-CoV-2. About 40% of symptomatic people consented to subsequent blood collection.

We saw the largest impact on older people who are at greater risk of death from COVID-19.

The observers found that just over 13% of people in the villages that received no interventions wore a mask properly, compared with more than 42% of people in the villages where each household received free masks and in-person reminders to wear them. Physical distancing was observed 24.1% of the time in control villages and 29.2% of the time in intervention villages.

About 7.6% of people in the intervention villages reported COVID-19 symptoms compared with about 8.6% of those in the control villages during the eight-week study period — a statistically significant difference that indicates a roughly 12% reduction in the risk of experiencing respiratory symptoms.

The researchers found that among the more than 350,000 people studied, the rate of people who reported symptoms of COVID-19, consented to blood collection and tested positive for the virus was 0.76% in the control villages and 0.68% in the intervention villages, showing an overall reduction in risk for symptomatic, confirmed infection of 9.3% in the intervention villages regardless of mask type.

When the researchers considered only those villages that received surgical masks (omitting villages that received cloth masks), the reduction in risk increased to 11%. Furthermore, the protective effect of surgical masks was greater for older people: As a group, those ages 50 to 60 were 23% less likely to develop COVID-19 if they wore a surgical mask, and those over 60 were 35% less likely if they did.

“This is statistically significant and, we believe, probably a low estimate of the effectiveness of surgical masks in community settings,” Styczynski said. The fact that the study was conducted at a time when the rate of transmission of COVID-19 in Bangladesh was relatively low, that a minority of symptomatic people consented to blood collection to confirm their disease status, and that fewer than half of the people in the intervention villages used facial coverings means the true impact of near-universal masking could be much more significant — particularly in areas with more indoor gatherings and events, she noted.

“If mask-wearing rates were higher, we would expect to see an even bigger impact on transmission,” Luby said. “But even at this level, we saw the largest impact on older people who are at greater risk of death from COVID-19.”

The interventions are now being rolled out in other parts of Bangladesh and in Pakistan, India, Nepal and parts of Latin America. But the researchers also hope there are lessons in the study for Americans.

“Unfortunately, much of the conversation around masking in the United States is not evidence-based,” Luby said. “Our study provides strong evidence that mask wearing can interrupt the transmission of SARS-CoV-2. It also suggests that filtration efficiency is important. This includes the fit of the mask as well as the materials from which it is made. A cloth mask is certainly better than nothing. But now might be a good time to consider upgrading to a surgical mask.”

The study was supported by a grant from GiveWell.org to Innovations for Poverty Action.

Researchers from Innovation for Poverty Action; the University of California-Berkeley; Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health; the NGRI North South University in Dhaka, Bangladesh; and Deakin University in Melbourne also contributed to the study.

Less

Stanford Medicine opens clinic for patients struggling with long COVID

With research showing up to 30% of COVID-19 patients experiencing lingering symptoms, Stanford Health Care treats such “long haulers” with multidisciplinary teams.

July 30, 2021 - By Tracie White

Hector Bonilla examines Rosie Flores at Stanford's Post-Acute COVID-19 Syndrome Clinic. Flores's health has improved since she started visiting the clinic, but some symptoms remain.

For about five months after contracting COVID-19, Rosie Flores lay on the couch at her home in Mountain View, California, feeling so fatigued that standing up was a struggle.

“I remember walking to my bed from the couch to grab a comforter and being out of breath,” said Flores, 47, who tested positive for the coronavirus in July 2020. “My arms felt like noodles. A phone conversation would exhaust me. My life was just living on the couch.”

Almost a year out, that fatigue has finally improved some. She went back to work part time in December as a project coordinator at Stanford Health Care, returning full time in March, but a day’s work still zaps her energy, and she continues to struggle with other symptoms, such as impaired memory, hair loss and balance problems.

In the fall, Flores was diagnosed at Stanford Health Care with symptoms of post-viral COVID-19 or, as it’s better known, long COVID. Unfortunately, she is not alone. As coronavirus cases have ebbed nationwide since the peak last winter, this newly described illness, estimated to affect up to 30% of recovering coronavirus patients, has caught the attention of the media, the federal government and the medical community, raising concerns that the long-term public health impact could be overwhelming.

At Stanford, some physicians who have been treating COVID-19 patients and researching long COVID realized they needed a clinic specifically for patients like Flores. Stanford Health Care’s Post-Acute COVID-19 Syndrome Clinic, or PACS, opened in May.

More

“As the pandemic progressed, we started seeing patients with all kinds of lingering symptoms after their initial COVID infection, including fatigue, dizziness, cognitive dysfunction, mood symptoms, chest pain, shortness of breath, insomnia, loss of taste and smell, hair loss and sleep disturbance,” said Linda Geng, MD, PhD, clinical assistant professor of medicine, who co-directs the clinic at Stanford. “It was clear this was a huge problem, and we needed to serve these patients.”

Lingering symptoms

Stories in the media about large numbers of patients who recovered from COVID-19, only to develop new and lingering symptoms, first appeared last summer. Some of the patients started calling themselves long-haulers, and the name stuck. Often, they said, they were dismissed by doctors who didn’t believe them.

The cause of long COVID remains unclear, and the number of people who suffer from it is unknown. It can persist for months and range from mild to incapacitating. There is no definitive lab test to diagnose it, and there are no standardized treatments. In many cases, patients are left wondering if they will ever get better.

Clinicians are taking cues from what is known about other chronic illnesses, such as myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome, a condition that often manifests after a viral infection and also has no known cause or standardized treatment, said Aruna Subramanian, MD, clinical professor of infectious disease at Stanford, who co-directs the ME/CFS Clinic. Long-COVID and ME/CFS symptoms are often similar and can include headaches and brain fog, as well as profound fatigue and something called post-exertional malaise — the worsening of symptoms after even minor physical or mental exertion.

Hector Bonilla and Linda Geng

Steve Fisch

“There seems to be a lot of overlap,” Subramanian said. “Working in the ME/CFS clinic, we see people who may have had other viral triggers, got sick … and their lives changed.”

Geng added that more research is needed to determine whether patients with long COVID fall into separate categories.

“This is a very heterogenous condition,” she said. “We may find different subgroups. There are patients who have multiple symptoms — dizziness, shortness of breath, insomnia all coming together — and then there are those with more isolated and defined COVID-specific symptoms like loss of smell and taste. The important thing to remember is to validate our patients; just because the condition is poorly understood doesn’t mean it’s not real.”

Whatever the case, enough scientific evidence has piled up to confirm that the problem is not only real but worrisome, according to the federal government. In December, Congress provided the National Institutes of Health with $1.15 billion to study the long-term symptoms of COVID-19. The NIH named the illness post-acute sequelae of SARS-CoV-2 infection and launched an initiative to find treatments.

“We do not know yet the magnitude of the problem, but given the number of individuals of all ages who have been or will be infected with SARS-CoV-2, the coronavirus that causes COVID-19, the public health impact could be profound,” Francis Collins, MD, PhD, director of the NIH, said in a press release announcing the initiative.

Studies providing evidence of the disorder first appeared in fall of 2020. In February, a study published in JAMA Open Network that followed COVID-19 patients up to nine months found about 30% reported persistent symptoms. A Nature Medicine article published in March, based on reports from 3,700 self-described long-haulers from 56 countries, showed nearly half couldn’t work full time for six months after first getting sick.

In May, a study by Stanford Medicine epidemiologists found that 70% of hospitalized COVID-19 patients had at least one symptom months later; another Stanford study found that even those with less severe cases of the virus, who were never hospitalized, were experiencing long COVID.

Physicians and scientists at Stanford continue to track symptoms and conduct imaging; they’re also searching for causes and treatments.

“There’s evidence the virus is triggering inflammation,” Subramanian said. “We know there is gastrointestinal involvement, but we don’t know much about these long-term symptoms in general — nausea, diarrhea, headaches. There seems to be some immune dysregulation. … We are wondering whether COVID is a trigger for ME/CFS.”

“We need new ideas so we can move treatment forward,” she added.

Just because the condition is poorly understood doesn't mean it's not real.

The PACS Clinic is designed to be a portal connecting long-COVID patients with a multidisciplinary team of post-COVID experts, including pulmonologists, cardiologists and neurologists, depending on symptoms. Some patients may have racing heartbeats and need to see a cardiologist. Many complain of shortness of breath and are referred to a pulmonologist. If a patient was hospitalized with COVID-19 and on a ventilator for a long period, the problem could be something called post-intensive care syndrome, and treatment could involve heart and lung and other rehabilitation.

Some patients have also been referred to the ME/CFS clinic, which can provide experimental medications, pain management techniques and activity-management training to help control the severe fatigue.

The co-directors of the PACS Clinic, Geng and Hector Bonilla, MD, clinical associate professor of infectious diseases, are experts in complex chronic diseases and post-viral illnesses. Geng’s expertise is in the diagnostic evaluation of patients with a wide variety of unexplained symptoms and mystery medical conditions, which is why long COVID caught her attention. She thought she could help by joining forces with other faculty members from various disciplines to tackle this complex condition, she said.

“When this condition came to light, it seemed very similar to many cases we had seen in our diagnotic clinic prior to COVID,” Geng said, referring to Stanford Health Care’s Consultative Care Clinic, which provides diagnostic services for patients with unexplained illnesses and symptoms. “We have seen patients with mysterious, puzzling symptoms after viral and other infectious illnesses. Long COVID can manifest in multiple systems of the body, including cardiopulmonary, endocrine, gastrointestinal, rheumatologic, neurologic, musculoskeletal, and so on.”

“We need to take a whole-body approach to patient care,” she added.

The long haul

Flores, who’s participating in a Stanford study of long COVID patients, has seen an array of specialists, including an audiologist, hematologist, cardiologist and pulmonologist. She’s been referred to a movement-disorders clinic. She’s discovered that she’s lost 10% to 15% of her hearing and that her balance is off. She has difficulty walking a straight line. No one knows why her hair keeps falling out.

“I feel like my memory has improved but not anywhere close to where it once was,” she said. There were times, especially in the early phase of her illness, when she would look at a word in print that she knew but couldn’t remember what it meant or how to pronounce it. A few times, she had difficulty speaking, and that scared her.

Most recently, she was given an off-label drug called aripiprazole that Bonilla studied in an earlier trial as an experimental treatment for ME/CFS. It gave her more energy and allowed her to work full time. Without it, she said, she wasn’t sure she could continue in her job.

“I was ready to give up, but those pills really helped,” she said. Still, her life is far from what it was before she got sick. She no longer volunteers at her church. A phone call to a friend can exhaust her. She can’t do a six-minute walk, and her balance remains unsteady. As each day passes, she grows more impatient for new research to provide better answers.

“You think it’s going to get better, but it doesn’t,” she said. “Everyone thinks you are doing well, but you’re not. My hair is still coming out in handfuls. If I close my eyes, I start swaying. That’s where I am right now.”

Less

Dean Winslow leads national COVID-19 Testing and Diagnostics Working Group

A professor of medicine and former Air Force colonel, Winslow temporarily relocated to Washington to head an interagency group responding to this pandemic and preparing for the next one.

JUL 20 2021 | JODY BERGER

In 2008, Dean Winslow holds an injured Iraqi child he was able to send to Shriners Burn Center in Boston.

Last fall, Dean Winslow, MD, saw the numbers everyone else saw: COVID-19 was killing nearly 2,000 Americans and infecting as many as 180,000 more each day. But he responded like few people could.

Winslow worked with state, federal and military leaders to get himself to Washington, D.C., where he now directs the COVID-19 Testing and Diagnostics Working Group, an 82-person, $46-billion interagency effort to track the virus and help steer the U.S. — and the world — out of the pandemic.

“I feel very lucky at this relatively late point in my career to be part of this,” said Winslow, who joined Stanford as a professor of medicine and as a senior fellow at the Freeman Spogli Institute for International Studies in 2013. “I had a wonderful 35 years in the military, and [serving in this role] almost feels like that, with the sense of purpose and camaraderie. And nobody’s shooting rockets at me.”

In November, with infections surging before vaccines were available, he wrote to Anne Schuchat, MD, the principal deputy director of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, volunteering to serve. But creating an official job within the federal government would take months.

Winslow couldn’t wait.

More

Joining the state guard

Winslow retired from the Air National Guard in 2015, but he came out of retirement in March 2020, joining the California State Guard to help with California’s COVID-19 response and train California Air National Guard members. After the CDC asked him to join the working group, the California State Guard put him on state active duty orders and sent him to the working group.

“When I joined the working group in April, I was probably the oldest officer on active duty in the United States,” the 68-year-old Winslow said.

“I got to wear camouflage pajamas to work again,” he added, using airmen’s vernacular for the uniforms they wear while deployed.

Winslow took a leave from Stanford to join the group and began leading the team July 1. By that point, he had an official civilian job, so he started dressing like the rest of the team that includes scientists from various specialties, data analysts, and acquisitions and logistics experts from the CDC, the Department of Health and Human Services, the National Institutes of Health, the Food and Drug Administration, and the Department of Defense.

The working group distributes testing resources, facilitates testing nationally, and tracks data from testing sites to know where the virus is infecting new communities and where new cases are occurring. The work has taken on increasing urgency in the past few weeks because of the more transmissible delta variant: Cases are surging again in parts of the country, especially where fewer residents are vaccinated.

Anthony Fauci and Dean Winslow share a friendship as well as a history of serving their country.

“As vaccination continues to slowly increase, the way we’re going to finally eliminate this pandemic, at least from the U.S., is by focusing on these hot spots, particularly among vulnerable populations,” Winslow said.

The group is also working with manufacturers to stockpile diagnostic testing equipment, which was in critically short supply during the height of the pandemic. Part of the longer-term goal is to provide incentives for U.S. manufacturers to keep their operations in the United States.

“We’re looking to make sure that we do a much, much better job in being prepared for the next pandemic,” Winslow said.

If tracking the current pandemic while also preparing for future events seems like an impossibly big job, it’s also a job that requires the rare combination of skills that Winslow has accumulated throughout his career. Even leading personnel with diverse skill sets — all on loan from other agencies — is in his wheelhouse.

“He’s got this ability to connect with everyone involved in this process,” said Julie Parsonnet, MD, professor of medicine and of health research and policy. (She’s also Winslow’s spouse.)

“He’s a welcoming collaborator, and he’s completely nonjudgmental,” she said.

A different virus

Winslow graduated from Pennsylvania State University and Jefferson Medical College before starting his internal medicine residency in Wilmington, Delaware. As a third-year resident, he was responsible for inviting speakers to give grand rounds, at which experts present medical cases and discuss treatment options. When a speaker backed out with only two days’ notice, Winslow called an immunologist at the National Institutes of Health who studied necrotizing vasculitis, a disorder that causes inflammation of the blood vessels.

The immunologist, Anthony Fauci, MD, agreed to give the talk if Winslow could pick him up at the Amtrak station and give him a lift back. Winslow accepted the deal, and the two men have been friends ever since. (Inviting Fauci to deliver the Thomas Merigan Lecture at Stanford in 2012, Winslow gave his old friend more notice.)

Winslow and Fauci, who is now chief medical adviser to President Joe Biden, are members of the last generation to train before the AIDS epidemic. The disease shaped both of their careers.

Winslow launched the first HIV clinic in Delaware. He had seen a patient with a compromised immune system and lesions on his brain during his first week in private practice in July 1981. There was no test for the virus at the time, but Winslow saved some of the patients’ blood serum and later learned that the man was, in fact, his first AIDS patient.

When AIDS testing became more readily available, Winslow started seeing more cases in socially vulnerable individuals and persuaded the administration of the Medical Center of Delaware to start the clinic. Later, while working in pharmaceutical-biotech industry, he also helped oversee trials of inhibitors to treat HIV and helped gain FDA clearance for a device that tests resistance to HIV drugs.

For his part, Fauci in 1984 became the director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, a position he still holds, and oversaw much of the AIDS research for the country.

Winslow joined the Louisiana Air National Guard in 1980, became a flight surgeon, then served as the state air surgeon in the Delaware National Guard. In 2008 he served as the commander at a combat hospital in Baghdad. He deployed four times to Iraq and twice to Afghanistan after 9/11 as a flight surgeon supporting combat operations.

“From the bottom airman on the ladder to the airmen wearing stars on their collars, Dean showed no preferential treatment,” said retired Brig. Gen. Bruce Thompson, who was Winslow’s commanding officer and has known him for 30 years. “Dean oozes compassion.”

When Winslow saw Iraqi children who could not receive the medical care they needed in Iraq, he arranged for them to be flown to the U.S. where hospitals could provide treatment.

In 2015, Winslow and Parsonnet created the Eagle Fund, a charitable trust that helps victims of war around the world.

“His whole career is about stepping up to the plate when asked,” Parsonnet said. “And even when he’s not asked.”

An honest answer

Four years ago, Winslow was nominated to become assistant secretary of defense for health affairs. In his senate confirmation hearing, Winslow fielded a question about a mass shooting that had just occurred in Texas. He answered honestly.

“I’d also like to … just say how insane it is that in the United States of America a civilian can go out and buy a semiautomatic weapon like an AR-15,” he said.

The late Sen. John McCain, R-Arizona, interrupted him to say this was not Winslow’s area of expertise, and soon the confirmation was put on indefinite hold. Winslow withdrew his name for consideration and turned his attention to helping victims of gun violence.

He worked with medical students and faculty to launch SAFE, Scrubs Addressing the Firearms Epidemic, a nonprofit organization of health care professionals dedicated to reducing gun violence and protecting the victims. SAFE now has chapters at more than 50 U.S. medical schools.

Winslow expects to stay with the working group for a year, then return to Stanford. The experience is reminiscent of other adventures he’s had in the military, in the clinic and in academia, he said. He’s surrounded by smart and dedicated colleagues, working together for a cause greater than themselves.

“I’ve had so many wonderful experiences in my life,” Winslow said. “I almost feel guilty for it. It’s like I’ve had more fun than any five people should have.”

Less

With herd immunity elusive, vaccination best defense against COVID-19, Stanford epidemiologist says

Epidemiology expert Julie Parsonnet warns that COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy has probably made herd immunity unattainable, which makes vaccination all the more important for personal health.

MAY 27 2021 | HANAE ARMITAGE

A focus on vaccinations rather than on herd immunity will help protect more people, epidemiologist Julie Parsonnet says.

COVID-19 vaccinations are now readily available to all Americans, so herd immunity should be attainable, right?

Probably not, says Julie Parsonnet, MD, professor of medicine and of epidemiology and population health. Paradoxically, it may be the very concept of herd immunity that is thwarting the uptake of vaccinations in the United States.

“We need to stop pushing herd immunity to the public,” Parsonnet said, as it may discourage some people from getting vaccinated in the mistaken belief that, if other people get vaccinated, they can just wait for herd immunity. “Public health departments don’t talk about herd immunity because it’s not helpful for the immediate protection of individuals and the overall response to the pandemic. What’s important is getting as many people vaccinated as you possibly can.”

More

Herd immunity is reached when the number of people in a population who are susceptible to disease drops to such a low level, usually due to vaccination, that any new cases cannot spread. Parsonnet, the George DeForest Barnett Professor in Medicine, said the concept of herd immunity is best used to model disease and figure out a public health strategy. Herd immunity is a nice idea, she said, but in reality, it’s a concept best applied to cow herds — or perhaps to nursing homes, ships, boarding schools or islands — but not to an entire country or the world.

Nevertheless, the concept caught the public’s attention last year as cases skyrocketed. Some have latched onto the idea, thinking that once the population reaches a certain threshold, the coronavirus will dissipate. But, while almost half the population of the United States has received at least one dose of a COVID-19 vaccine, hesitancy is high — about 30% — and a vaccine rate of 70% won’t bring us close to herd immunity, Parsonnet said.

COVID-19 is not measles

Diseases such as measles and smallpox have been nearly eradicated, or at least heavily tamped down, thanks to widespread and effective vaccination. It’s unlikely the United States has actually reached herd immunity for measles, as many children are now unvaccinated, Parsonnet said. “Measles cases are currently quite rare, and when they do occur, they’re always symptomatic. This allows for those who’ve been exposed to be isolated, and those at risk can be protected through something called ‘ring vaccination,’ in which people who may encounter a sick individual are vaccinated,” she said.

But COVID-19 is not measles. Unlike measles, not all cases of COVID-19 are symptomatic, so sick individuals can’t all be isolated; the COVID-19 vaccine is not 100% effective, and it’s unknown how long it bestows protection; there are many variants of the virus; and the virus can infect animals. “It took 40 years to control measles; for COVID, it is likely to take a lot longer to control,” Parsonnet said.

“The other important thing to remember is that herd immunity is not this ah-ha moment where suddenly there’s no more disease and we don’t have to worry about it anymore,” Parsonnet said. “It’s something that must be maintained, mostly through vaccinations, once transmission has slowed down.”

The need for immunological upkeep is due to new “susceptibles,” or individuals who have no immunity to a given disease, in a population. And with regard to COVID-19, there are a lot of susceptibles, such as newborns or immunosuppressed individuals. “We don’t live in isolation, and to get herd immunity in such an interconnected world is extremely challenging,” Parsonnet said.

It’s true that susceptible individuals who acquire COVID-19 will have natural immunity, but it’s not enough to protect the herd. Parsonnet uses measles to illustrate her point. The disease was introduced in the Americas in the 1500s, but even after hundreds of years, the U.S. population never developed natural herd immunity, likely due to newborns’ natural susceptibility, among other reasons. Only after 1963, when a measles vaccine was developed, did the United States start seeing large-scale immunity. For SARS-CoV-2, it’s even trickier, as variants could evade natural or vaccine-derived immunity, and natural immunity doesn’t seem to be as potent, Parsonnet said.

Stop planning on herd immunity

Parsonnet also is concerned that vaccine hesitancy remains high in the United States. Using an equation that estimates the transmissibility COVID-19 and the effectiveness of the available vaccines, her latest calculations show that about 90% of the United States would need to be fully vaccinated to reach herd immunity. There are other challenges as well.

“What if vaccine immunity starts to wane? What if we all need booster shots for a different variant?” she said. Every time booster shots are required, she noted, there’s likely to be a dip in the number of people showing up to receive them.

So, what are we to do?

“The best way to handle this is to vaccinate the people who are most likely to transmit the virus — young adults, people who have a lot of contacts, people who live with a lot of other people in their households,” Parsonnet said.

People who are reluctant to get the vaccine and people who face obstacles to receiving it, such as immigrants who experience language barriers, are most likely to transmit the virus. Vaccination campaigns should focus on those groups, Parsonnet said.

“If we want to approach this in a realistic way, the focus shouldn’t be on herd immunity. It should be on vaccinating as many people as possible — especially the people who will have the biggest impact on a population level,” Parsonnet said. “That’s what will make the biggest impact on significantly diminishing the rates of COVID-19.”

Less

5 Questions: David Relman on investigating origin of coronavirus

Microbiologist David Relman explores how the coronavirus could have emerged and why we need to know.

MAY 20 2021 | BRUCE GOLDMAN

On May 13, the journal Science published a letter, signed by 18 scientists, stating that it was still unclear whether the virus that causes COVID-19 emerged naturally or was the result of a laboratory accident, but that neither cause could be ruled out. David Relman, MD, the Thomas C. and Joan M. Merigan Professor and professor of microbiology and immunology, spearheaded the effort.

Relman is no stranger to complicated microbial threat scenarios and illness of unclear origin. He has advised the U.S. government on emerging infectious diseases and potential biological threats. He served as vice chair of a National Academy of Sciences committee reviewing the FBI investigation of letters containing anthrax that were sent in 2001. Recently, he chaired another academy committee that assessed a cluster of poorly explained illnesses in U.S. embassy employees. He is a past president of the Infectious Diseases Society of America.

Stanford Medicine science writer Bruce Goldman asked Relman to explain what remains unknown about the coronavirus’s emergence, what we may learn and what’s at stake.

1. How might SARS-CoV-2, which causes COVID-19, have first infected humans?

Relman: We know very little about its origins. The virus’s closest known relatives were discovered in bats in Yunnan Province, China, yet the first known cases of COVID-19 were detected in Wuhan, about 1,000 miles away.

There are two general scenarios by which this virus could have made the jump to humans. First, the jump, or “spillover,” might have happened directly from an animal to a human, by means of an encounter that took place within, say, a bat-inhabited cave or mine, or closer to human dwellings — say, at an animal market. Or it could have happened indirectly, through a human encounter with some other animal to which the primary host, presumably a bat, had transmitted the virus.

Bats and other potential SARS-CoV-2 hosts are known to be shipped across China, including to Wuhan. But if there were any infected animals near or in Wuhan, they haven’t been publicly identified.

Maybe someone became infected after contact with an infected animal in or near Yunnan, and moved on to Wuhan. But then, because of the high transmissibility of this virus, you’d have expected to see other infected people at or near the site of this initial encounter, whether through similar animal exposure or because of transmission from this person.

2. What’s the other scenario?

Relman: SARS-CoV-2 could have spent some time in a laboratory before encountering humans. We know that some of the

More

largest collections of bat coronaviruses in the world — and a vigorous research program involving the creation of “chimeric” bat coronaviruses by integrating unfamiliar coronavirus genomic sequences into other, known coronaviruses — are located in downtown Wuhan. And we know that laboratory accidents happen everywhere there are laboratories.

All scientists need to acknowledge a simple fact: Humans are fallible, and laboratory accidents happen — far more often than we care to admit. Several years ago, an investigative reporter uncovered evidence of hundreds of lab accidents across the United States involving dangerous, disease-causing microbes in academic institutions and government centers of excellence alike — including the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the National Institutes of Health.

SARS-CoV-2 might have been lurking in a sample collected from a bat or other infected animal, brought to a laboratory, perhaps stored in a freezer, then propagated in the laboratory as part of an effort to resurrect and study bat-associated viruses. The materials might have been discarded as a failed experiment. Or SARS-CoV-2 could have been created through commonly used laboratory techniques to study novel viruses, starting with closely related coronaviruses that have not yet been revealed to the public. Either way, SARS-CoV-2 could have easily infected an unsuspecting lab worker and then caused a mild or asymptomatic infection that was carried out of the laboratory.

3. Why is it important to understand SARS-CoV-2’s origins?

Relman: Some argue that we would be best served by focusing on countering the dire impacts of the pandemic and not diverting resources to ascertaining its origins. I agree that addressing the pandemic’s calamitous effects deserves high priority. But it’s possible and important for us to pursue both. Greater clarity about the origins will help guide efforts to prevent a next pandemic. Such prevention efforts would look very different depending on which of these scenarios proves to be the most likely.

Evidence favoring a natural spillover should prompt a wide variety of measures to minimize human contact with high-risk animal hosts. Evidence favoring a laboratory spillover should prompt intensified review and oversight of high-risk laboratory work and should strengthen efforts to improve laboratory safety. Both kinds of risk-mitigation efforts will be resource intensive, so it’s worth knowing which scenario is most likely.

4. What attempts at investigating SARS-CoV-2’s origin have been made so far, with what outcomes?

Relman: There’s a glaring paucity of data. The SARS-CoV-2 genome sequence, and those of a handful of not-so-closely-related bat coronaviruses, have been analyzed ad nauseam. But the near ancestors of SARS-CoV-2 remain missing in action. Absent that knowledge, it’s impossible to discern the origins of this virus from its genome sequence alone. SARS-CoV-2 hasn’t been reliably detected anywhere prior to the first reported cases of disease in humans in Wuhan at the end of 2019. The whole enterprise has been made even more difficult by the Chinese national authorities’ efforts to control and limit the release of public health records and data pertaining to laboratory research on coronaviruses.

In mid-2020, the World Health Organization organized an investigation into the origins of COVID-19, resulting in a fact-finding trip to Wuhan in January 2021. But the terms of reference laying out the purposes and structure of the visit made no mention of a possible laboratory-based scenario. Each investigating team member had to be individually approved by the Chinese government. And much of the data the investigators got to see was selected prior to the visit and aggregated and presented to the team by their hosts.

The recently released final report from the WHO concluded — despite the absence of dispositive evidence for either scenario — that a natural origin was “likely to very likely” and a laboratory accident “extremely unlikely.” The report dedicated only 4 of its 313 pages to the possibility of a laboratory scenario, much of it under a header entitled “conspiracy theories.” Multiple statements by one of the investigators lambasted any discussion of a laboratory origin as the work of dark conspiracy theorists. (Notably, that investigator — the only American selected to be on the team — has a pronounced conflict of interest.)

Given all this, it’s tough to give this WHO report much credibility. Its lack of objectivity and its failure to follow basic principles of scientific investigation are troubling. Fortunately, WHO’s director-general recognizes some of the shortcomings of the WHO effort and has called for a more robust investigation, as have the governments of the United States, 13 other countries and the European Union.

5. What’s key to an effective investigation of the virus’s origins?

Relman: A credible investigation should address all plausible scenarios in a deliberate manner, involve a wide variety of expertise and disciplines and follow the evidence. In order to critically evaluate other scientists’ conclusions, we must demand their original primary data and the exact methods they used — regardless of how we feel about the topic or about those whose conclusions we seek to assess. Prior assumptions or beliefs, in the absence of supporting evidence, must be set aside.

Investigators should not have any significant conflicts of interest in the outcome of the investigation, such as standing to gain or lose anything of value should the evidence point to any particular scenario.

There are myriad possible sources of valuable data and information, some of them still preserved and protected, that could make greater clarity about the origins feasible. For all of these forms of data and information, one needs proof of place and time of origin, and proof of provenance.

To understand the place and time of the first human cases, we need original records from clinical care facilities and public health institutions as well as archived clinical laboratory data and leftover clinical samples on which new analyses can be performed. One might expect to find samples of wildlife, records of animal die-offs and supply-chain documents.

Efforts to explore possible laboratory origins will require that all laboratories known to be working on coronaviruses, or collecting relevant animal or clinical samples, provide original records of experimental work, internal communications, all forms of data — especially all genetic-sequence data — and all viruses, both natural and recombinant. One might expect to find archived sequence databases and laboratory records.

Needless to say, the politicized nature of the origins issue will make a proper investigation very difficult to pull off. But this doesn’t mean that we shouldn’t try our best. Scientists are inquisitive, capable, clever, determined when motivated, and inclined to share their insights and findings. This should not be a finger-pointing exercise, nor an indictment of one country or an abdication of the important mission to discover biological threats in nature before they cause harm. Scientists are also committed to the pursuit of truth and knowledge. If we have the will, we can and will learn much more about where and how this pandemic arose.

Less

Stanford Health Care Receives the IDSA Antimicrobial Stewardship Centers of Excellence Designation

Stanford Health Care has been awarded the designation of Antimicrobial Stewardship Centers of Excellence (CoE) by the Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA). The CoE program recognizes institutions that have created stewardship programs led by infectious diseases physicians and ID-trained pharmacists that are of the highest quality and have achieved standards aligned with evidence-based national guidelines such as the IDSA-SHEA guidelines and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s Core Elements. Stanford Health Care is one of 41 programs nationwide to have received the designation since the program’s launch in 2017.

“Each year, more than 700,000 people worldwide die due to antimicrobial-resistant infections. Antimicrobial resistance is one of the greatest threats facing healthcare on a global, national and individual level. IDSA is committed to fighting antimicrobial resistance through its research, education, training, and policy efforts. IDSA is proud to partner with Institution and others that have received the Centers of Excellence designation in turning the tide against antimicrobial resistance,” said IDSA President Cynthia Sears, MD, FIDSA.

The core criteria for the CoE program place emphasis on an institution’s ability to implement stewardship protocols to optimize the treatment of infections and reduce adverse events associated with antibiotic use leveraging electronic health record systems and providing ongoing education to help clinicians improve the quality of patient care and promote patient safety. A panel of esteemed IDSA member leaders evaluate CoE applications against core criteria to make recommendations for the designation. The panel is comprised of five ID-trained physicians and three ID-trained pharmacists with many years of expert stewardship experience.

Click here for details of Stanford Health Care's Antimicrobial Stewardship Program.

Click here to learn more about the IDSA Antimicrobial Stewardship Centers of Excellence program.

About the IDSA

The Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA) represents physicians, scientists and other health care professionals who specialize in infectious diseases.

IDSA’s purpose is to improve the health of individuals, communities, and society by promoting excellence in patient care, education, research, public health, and prevention relating to infectious diseases.

Set of genes predicts severity of dengue

By HANAE ARMITAGE | January 29, 2019

There’s no such thing as a “good” case of dengue fever, but some are worse than others, and it’s difficult to determine which patients will make a smooth recovery and which may find their condition life-threatening.

Now, after scouring the gene expression of hundreds of patients infected with dengue virus — a mosquito-borne virus that can cause fever and joint pain, among other symptoms — scientists at the Stanford University School of Medicine have found a set of 20 genes that predicts who is at the highest risk of progressing to a severe form of the illness.

Every year, between 200 million and 400 million people in tropical and subtropical regions of the world contract dengue fever, and about 500,000 of those cases are fatal. For the most part, people with the disease recover after receiving some fluids and a few days’ rest, said Purvesh Khatri, PhD, associate professor of medicine and of biomedical data science. “But there’s a smaller subset of patients who get severe dengue, and right now we don’t know how to tell the difference.”

Anywhere from 5 to 20 percent of dengue cases will advance to severe. Currently, the standard of care boils down to watching and waiting: To diagnose severe dengue, doctors wait to observe specific symptoms and results of laboratory tests that typically emerge in the late stages of the disease. “These practices are not nearly sensitive or accurate enough, and some patients end up admitted to the hospital unnecessarily, while others are discharged prematurely,” said Shirit Einav, MD, associate professor of medicine and of microbiology and immunology.

Using their newly identified set of genes as a foundation, Einav and Khatri aim to identify predictive biomarkers that can help doctors reliably gauge the likelihood of severe dengue in patients who are newly symptomatic and use that information to provide more accurate care to help guide therapeutic clinical studies and, in the future, to guide treatment decisions.

A paper detailing the study’s findings were published Jan. 29 in Cell Reports. Einav and Khatri are co-senior authors. Graduate student Makeda Robinson, MD, and former research associate Timothy Sweeny, MD, PhD, share lead authorship.

More Mining old data

Adept at sleuthing out new findings from old data, Khatri used five previously published papers, which reported information on about 450 individuals collectively, to identify the severe-dengue gene set. Each study catalogued groups of dengue patients, tracking the “transcriptome,” or record of gene expression, at the onset of symptoms for each case.

Purvesh Khatri

“The papers had data on dengue patients from multiple countries. We looked at the data and asked, ‘Irrespective of the patient’s genetic background, age and the genetics of the dengue virus itself — different regions have different forms of dengue — what is the molecular response that always shows up when you have a dengue infection?’” Khatri said. “But we weren’t comparing healthy versus infected patients; we compared those who had an uncomplicated dengue infection with those who developed severe dengue.”

In analyzing data from the five studies, Khatri and Einav identified 20 genes that stood out. In all of the patients who developed severe dengue, these genes showed a specific expression pattern, or signature: Seventeen were underexpressed, whereas three were overactive. But predicting severe dengue is more complex than whether patients expressed this pattern; there’s variability. Some of the genes were down-regulated to a greater extent in some patients, and less so in others; likewise, there was variability in the degree of overactivity in the overexpressed genes.

“This prediction method is more of a continuum than a binary,” Khatri said. To make sense of the continuum, the researchers developed a score that accounted for this gene-expression variability, essentially evaluating the patients’ risk for severe dengue based on dips and peaks of expression in these 20 genes. The higher the score, the higher the risk of severe dengue.

Then they tested their dengue-prediction method on data from three separate, previously published cohorts of dengue patients, whose transcriptome data was public, and found that the 20-gene set predicted 100 percent of the patients who developed severe dengue. Among those predicted to come down with severe dengue, 78 percent did.

Testing the test

Next, the researchers wanted to see if their predictive measure would succeed in a real-world patient population. So in partnership with the Clinical Research Center of the Valle del Lili Foundation, in Colombia, they set up a prospective cohort of 34 participants with dengue to assess the efficacy of the predictive gene markers. Each of participants’ transcriptome information, which came from a simple blood draw, yielded a predictive score based on the 20-gene set, and again, Einav and Khatri saw the same levels of accuracy in their test: The test predicted the participants with severe dengue, and there were only a few patients predicted to develop severe dengue who did not.

“Of course, these population samples are small, and we want to confirm our findings in larger cohorts,” Khatri said. The researchers plan to conduct larger trials as they aim to bring the evaluation into clinical use. They’re already expanding trials into Paraguay.

There’s no perfect test, but we’re encouraged by these numbers.

“With a larger cohort, there’s also an opportunity to refine the signature; we could potentially bring down the number of genes,” Einav said. “There’s no perfect test, but we’re encouraged by these numbers, and this is already performing better than the current standard of care.”

It’s likewise possible that the genes could serve as a basis for a targeted therapy for dengue, Einav said — but that’s far on the horizon. For now, the researchers are starting to pursue the mechanisms behind these 20 genes, trying to understand why they seem to foretell the fate of dengue patients.

The work is an example of Stanford Medicine’s focus on precision health, the goal of which is to anticipate and prevent disease in the healthy and precisely diagnose and treat disease in the ill.

Other Stanford co-authors are research associate Rina Barouch-Bentov, PhD; research scientist Malaya Sahoo, PhD; graduate student Larry Kalesinskas; postdoctoral scholar Francesco Valliania, PhD; Jose Montoya, MD, professor of medicine; and Benjamin Pinsky, PhD, associate professor of pathology.

Researchers from the Valle del Lili Foundation also contributed to the research.

The study was funded by Stanford Bio-X; the Stanford Translational Research and Applied Medicineprogram; Stanford SPARK; the Stanford Maternal & Child Health Research Institute; the Stanford Institute for Immunity, Transplantation and Infection; the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation; Vir Bio; and the National Institutes of Health (grants AI125197, U19AI109662 and U19AI057229).

Stanford’s departments of Medicine, of Microbiology and Immunology, and of Biomedical Data Science also supported the work.

The Health Trust hosts the 3rd Annual World AIDS Day Benefit Dinner

The event is a benefit for the Health Trust AIDS Services program and honors professionals for their service to individuals with HIV in the community.

This year, they honored Dr. Larry Mc Glynn with the Red Ribbon Award for outstanding service to individuals with HIV/AIDS. The Health Trust AIDS Services staff and many community partners in the field acknowledge Dr. Mc Glynn's expertise, compassion and longstanding commitment to people with HIV/AIDS in our community.

Dr. Mc Glynn is a Clinical Professor in the Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences at Stanford University. Since 2000, he has served as the Director of the HIV Mental Health Program at Stanford's Positive Care Clinic.

Researchers identify biomarkers associated with chronic fatigue syndrome severity

Stanford investigators used high-throughput analysis to link inflammation to chronic fatigue syndrome, a difficult-to-diagnose disease with no known cure.

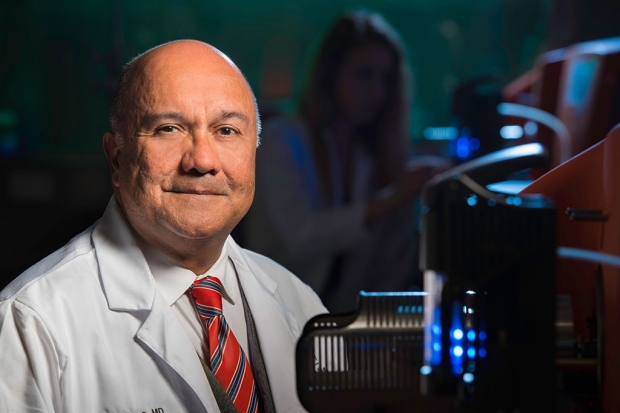

Jose Montoya and his colleagues have found evidence inflammation may be the culprit behind chronic fatigue syndrome, a disease with no known cure.

Steve Fisch

Researchers at the Stanford University School of Medicine have linked chronic fatigue syndrome to variations in 17 immune-system signaling proteins, or cytokines, whose concentrations in the blood correlate with the disease’s severity.

The findings provide evidence that inflammation is a powerful driver of this mysterious condition, whose underpinnings have eluded researchers for 35 years.

The findings, described in a study published online July 31 in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, could lead to further understanding of this condition and be used to improve the diagnosis and treatment of the disorder, which has been notably difficult.

More than 1 million people in the United States suffer from chronic fatigue syndrome, also known as myalgic encephomyelitis and designated by the acronym ME/CFS. It is a disease with no known cure or even reliably effective treatments. Three of every four ME/CFS patients are women, for reasons that are not understood. It characteristically arises in two major waves: among adolescents between the ages of 15 and 20, and in adults between 30 and 35. The condition typically persists for decades.

“Chronic fatigue syndrome can turn a life of productive activity into one of dependency and desolation,” said Jose Montoya, MD, professor of infectious diseases, who is the study’s lead author. Some spontaneous recoveries occur during the first year, he said, but rarely after the condition has persisted more than five years.

The study’s senior author is Mark Davis, PhD, professor of immunology and microbiology and director of Stanford’s Institute for Immunity, Transplantation and Infection. More

‘Solid basis for a diagnostic blood test’

“There’s been a great deal of controversy and confusion surrounding ME/CFS — even whether it is an actual disease,” said Davis. “Our findings show clearly that it’s an inflammatory disease and provide a solid basis for a diagnostic blood test.”

Many, but not all, ME/CFS patients experience flulike symptoms common in inflammation-driven diseases, Montoya said. But because its symptoms are so diffuse —sometimes manifesting as heart problems, sometimes as mental impairment nicknamed “brain fog,” other times as indigestion, diarrhea, constipation, muscle pain, tender lymph nodes and so forth — it often goes undiagnosed, even among patients who’ve visited a half-dozen or more different specialists in an effort to determine what’s wrong with them.

Mark Davis

Montoya, who oversees the Stanford ME/CFS Initiative, came across his first ME/CFS patient in 2004, an experience he said he’s never forgotten.

“I have seen the horrors of this disease, multiplied by hundreds of patients,” he said. “It’s been observed and talked about for 35 years now, sometimes with the onus of being described as a psychological condition. But chronic fatigue syndrome is by no means a figment of the imagination. This is real.”

Antivirals, anti-inflammatories and immune-modulating drugs have led to symptomatic improvement in some cases, Montoya said. But no single pathogenic agent that can be fingered as the ultimate ME/CFS trigger has yet been isolated, while previous efforts to identify immunological abnormalities behind the disease have met with conflicting and confusing results.

Still, the sporadic effectiveness of antiviral and anti-inflammatory drugs has spurred Montoya to undertake a systematic study to see if the inflammation that’s been a will-o’-the-wisp in those previous searches could be definitively pinned down.

To attack this problem, he called on Davis, who helped create the Human Immune Monitoring Center. Since its inception a decade ago, the center has served as an engine for large-scale, data-intensive immunological analysis of human blood and tissue samples. Directed by study co-author Holden Maecker, PhD, a professor of microbiology and immunology, the center is equipped to rapidly assess gene variations and activity levels, frequencies of numerous immune cell types, blood concentrations of scores of immune proteins, activation states of intercellular signaling models, and more on a massive scale.

Finding patterns

This approach is akin to being able to look for and find larger patterns — analogous to whole words or sentences — in order to locate a desired paragraph in a lengthy manuscript, rather than just try to locate it by counting the number of times in which the letter A appears in every paragraph.

The scientists analyzed blood samples from 192 of Montoya’s patients, as well as from 392 healthy control subjects. The average age of patients and controls was about 50. Patients’ average duration of symptoms was somewhat more than 10 years.

Importantly, the study design took into account patients’ disease severity and duration. The scientists found that some cytokine levels were lower in patients with mild forms of ME/CFS than in the control subjects, but elevated in ME/CFS patients with relatively severe manifestations. Averaging the results for patients versus controls with respect to these measures would have obscured this phenomenon, which Montoya said he thinks may reflect different genetic predispositions, among patients, to progress to mild versus severe disease.

I have seen the horrors of this disease, multiplied by hundreds of patients.

I have seen the horrors of this disease, multiplied by hundreds of patients.

When comparing patients versus control subjects, the researchers found that only two of the 51 cytokines they measured were different. Tumor growth factor beta was higher and resistin was lower in ME/CFS patients. However, the investigators found that the concentrations of 17 of the cytokines tracked disease severity. Thirteen of those 17 cytokines are pro-inflammatory.

TGF-beta is often thought of as an anti-inflammatory rather than a pro-inflammatory cytokine. But it’s known to take on a pro-inflammatory character in some cases, including certain cancers. ME/CFS patients have a higher than normal incidence of lymphoma, and Montoya speculated that TGF-beta’s elevation in ME/CFS patients could turn out to be a link.

One of the cytokines whose levels corresponded to disease severity, leptin, is secreted by fat tissue. Best known as a satiety reporter that tells the brain when somebody’s stomach is full, leptin is also an active pro-inflammatory substance. Generally, leptin is more abundant in women’s blood than in men’s, which could throw light on why more women than men have ME/CFS.

More generally speaking, the study’s results hold implications for the design of future studies of disease, including clinical trials testing immunomodulatory drugs’ potential as ME/CFS therapies.

“For decades, the ‘case vs. healthy controls’ study design has served well to advance our understanding of many diseases,” Montoya said. “However, it’s possible that for certain pathologies in humans, analysis by disease severity or duration would be likely to provide further insights.”

Other Stanford co-authors of the study are clinical research coordinator Jill Anderson; Tyson Holmes, PhD, senior research engineer at the Institute for Immunity, Transplantation and Infection; Yael Rosenberg-Hasson, PhD, immunoassay and technical director at the institute; Cristina Tato, PhD, MPH, research and science analyst at the institute; former study coordinator Ian Valencia; and Lily Chu, MSHS, a board member of the Stanford University ME/CFS Initiative.

The study was funded by the National Institutes of Health (grant U19AI057229), the Stanford ME/CFS Initiative Fund and an anonymous donor.

Stanford’s departments of Medicine and of Microbiology and Immunology also supported the work.

By Bruce Goldman via Stanford Medicine News Center

Dr. Dean Winslow receives the IDSA Society Citation

Dean Winslow, MD, FIDSA

Society Citation Dean L. Winslow, MD, FIDSA, a compassionate, committed clinician, teacher, and military veteran who has been a champion for patients with HIV and victims of war and disaster, is the recipient of a 2017 IDSA Society Citation. First awarded in 1977, this is a discretionary award given in recognition of exemplary contribution to IDSA, an outstanding discovery in the field of infectious diseases, or a lifetime of outstanding achievement.

Dr. Winslow is vice chair of the Department of Medicine and a professor of medicine in the Division of Hospital Medicine and the Division of Infectious Diseases and Geographic Medicine at Stanford University, where he has been on the faculty since 1998. He is also academic physician-in-chief at Stanford/ValleyCare, a community teaching hospital. His professional career began in private practice in Delaware, where he started the state’s first multidisciplinary clinic for HIV-infected patients in 1985. During his later time in industry, he worked on studies of HIV drug resistance as a bench scientist and designed the clinical trials leading to the Food and Drug Administration’s approval of efavirenz. He also helped direct the clinical studies of nelfinavir and led the group responsible for regulatory approval of the first pharmacogenomics diagnostic device for HIV-1 drug resistance.

Before returning to Stanford fulltime in 2013, Dr. Winslow was chief of the Division of AIDS Medicine and chair of the Department of Medicine at Santa Clara Valley Medical Center, the institution’s largest academic and clinical unit. In addition to caring for adults, Dr. Winslow regularly attended on the pediatric infectious diseases consult service at the county hospital. From 2003 to 2011, Dr. Winslow also deployed to Iraq and Afghanistan six times as a flight surgeon in the Air National Guard in support of combat operations there, including serving as the commander of an Air Force combat hospital unit in Baghdad in 2008. Closer to home, he coordinated military public health and force protection in Louisiana after Hurricane Katrina. He has been awarded numerous military decorations for his service.

In addition to his care for wounded service personnel in the Middle East, Dr. Winslow also treated many local civilians. A passionate supporter of human rights and health, he has, since 2006, arranged for medical care, transportation, and housing in the U.S. for more than 20 Iraqi children and adults with complicated medical conditions for which surgical care was not available in Iraq. He has been recognized by the Iraqi Army for his humanitarian service to the Iraqi people and was named a Paul Harris Fellow by Rotary International.

After earning his medical degree from Jefferson Medical College in Philadelphia, Dr. Winslow completed his internship and residency in internal medicine at the Medical Center of Delaware, followed by a fellowship in infectious diseases at the Ochsner Clinic in New Orleans. A highly regarded attending physician on the ID consultation services at Stanford and the Palo Alto Veterans Administration Medical Center, Dr. Winslow has received multiple teaching awards. His wide-ranging knowledge and experience, combined with his passion for teaching and patient care, are legendary among ID fellows and residents. The author of more than 60 peer- reviewed publications and more than 90 presentations at national and international meetings, he is the current chair of IDSA’s Standards and Practice Guidelines Committee.

Dr. Winslow’s extensive knowledge, deep compassion, and wide-ranging experience over more than four decades have greatly impacted patients around the world, his colleagues, and the next generation of ID physicians. The Society is delighted to add a 2017 Society Citation to his long list of accomplishments

Paul Bollyky Receives Harrington Scholar-Innovator Grant

Source: Department of Medicine News

Harrington Discovery Institute has selected Paul Bollyky, MD, (assistant professor, infectious diseases) as one of its 2017 Scholar-Innovators. Chosen for his work on a novel drug for Type I Diabetes, Bollyky is one of 11 awardees this year.