November 2, 2009 - By Erin Digitale

Packard Children's neonatologist Anna Penn examines the role of the placenta in brain development

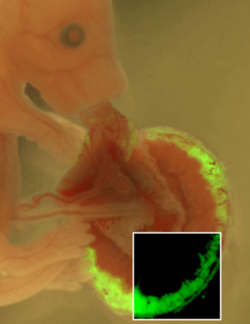

Anna Penn’s lab genetically modified the placenta beside this mouse embryo to see its effect on development. A green fluorescent tag (detail) shows that the change is limited to the placenta.

Before miniature ventilators and artificial lung surfactant, doctors struggled to help premature infants breathe. Now, neonatologists are tackling a daunting new problem: The tiny preemies saved by modern respiratory support often go on to suffer neurologic deficits.

“The question is,” said Packard Children’s neonatologist Anna Penn, MD, PhD, “what do you do about long-term development?”

Penn believes the answer lies in the placenta, whose rich soup of hormones has scarcely been studied. In the past, the placenta was viewed as expendable – just something that ends up in a bucket. Penn sees the organ differently, hypothesizing preemies’ early loss of placental hormones hobbles their developing brains. Her laboratory is gearing up to study the exact role of the placenta in brain development.

“We’re asking, physiologically, what should these kids be exposed to from the placenta? And will they benefit if we give back what they’ve lost?” she said.

Penn’s team recently received a five-year, $1.5 million grant from the National Institutes of Health to examine the role of placental hormones in fetal brain development. Starting with a list of 100 peptide and steroid hormones manufactured in the placenta, the scientists are developing genetically engineered mice in which they can withdraw one placental hormone at a time at distinct stages of development. They’ll look for evidence of neurological deficits in the brain structure and behavior of mice subjected to these changes in utero. For instance, humans born prematurely often exhibit signs of autism, such as social or behavioral difficulties, so the researchers will look for similar changes in their mice. The project is the first-ever comprehensive effort to measure how placental hormones change the fetal brain.

In the hospital, Penn and her colleagues are starting a study to collect small amounts of blood and spinal fluid from infants already having these fluids drawn for clinical reasons. The researchers will measure hormones present in the two fluids, comparing preemies and full-term infants to look for hormone patterns characteristic of prematurity.

Penn’s team is also starting a placenta bank, a joint effort of Packard Children’s Hospital and the Stanford School of Medicine. The scientists plan to store small pieces of donated placental tissue; extracted DNA, RNA and protein from the placentas; and a database of health information on the moms and babies the placentas belonged to. Over the next few years, the team hopes to build the placenta bank into thousands of specimens that can function as a nationally-accessible scientific tool.

“If people are willing to donate normal placentas, preterm placentas and pre-eclamptic placentas, we’ll be able to build a very broad resource that will provide for all different avenues of research,” Penn said.

Though she believes the basic and clinical science will take 15 to 20 years, Penn hopes her efforts will eventually pay off with a straightforward method for preventing neurological problems in preemies.

“Ideally, we would be able to take either blood or spinal fluid, profile the levels of hormones that we know are important for normal brain development, and give back those that were not there in adequate amounts,” Penn said. “That’s the fantasy – a simple and quick diagnostic and replacement.”

About Stanford Medicine

Stanford Medicine is an integrated academic health system comprising the Stanford School of Medicine and adult and pediatric health care delivery systems. Together, they harness the full potential of biomedicine through collaborative research, education and clinical care for patients. For more information, please visit med.stanford.edu.