Technologies

Awair Reducing Sedation for Patients on Respiratory Support –

An Interview with Rush Bartlett and Ryan Van Wert of Awair

What is the need you set out to address?

Rush: During the early days of our fellowship year, we did our clinical immersion in the ICU. On one of our first observation days, we saw a patient who was intubated and on a ventilator. As an engineer without much clinical exposure, I noticed that his mouth was wide open to accommodate the tube, and I couldn’t help wondering what would happen if a bug were to crawl or fly into the opening. What we learned is that his mouth was open because he was unconscious. And the reason he was unconscious wasn’t that he was so sick, it was because the endotracheal tube is so uncomfortable that patients have to be placed in a drug-induced coma to tolerate it.

Three or four weeks later, we happened to go to a Grand Rounds talk on the costly and debilitating consequences of intravenous sedation. We learned that not only are the drugs to maintain this condition expensive, costing up to $800 per day, they are routinely linked to serious complications, including ventilator-associated pneumonia, pressure ulcers, muscle atrophy and delirium – all of which can add significant costs and months of rehabilitation to a patient’s recovery. So the pieces started to come together. Our need statement ended up being, ‘A way to eliminate discomfort from an endotracheal tube without an intravenous sedative for patients who are receiving respiratory support in order to reduce the complications associated with intravenous sedation.’

What key insight was most important to guiding the design of your solution?

Ryan: First, we observed other procedures in the hospital, namely bronchoscopy, where a scope that’s similar in size to an endotracheal tube was passed through similar airway structures, using only a local, topical anesthetic in the upper airway. And patients were able to tolerate this without the need for heavy sedation.

“…we needed to have a way to deliver the medication on more of a continuous basis without obligating a clinician to manually apply it.”

Second, when we looked into the literature to see if anyone had studied this as an alternative for patients on respiratory support, we found a few anesthesiologists who had either sprayed a topical anesthetic on the lining of the throat and found that it reduced the need for sedation or had put what are called nerve blocks in place and determined that patients who needed a tube in place after a surgery were far more comfortable and needed less sedation. However, the issue with both of these approaches was that they required manual intervention and so didn't fit well into the clinical workflow and weren’t widely adopted.

How does your solution work?

Rush: Building on prior studies in the space, we focused on the use of a local anesthetic – lidocaine, which is a dental anesthetic – to numb the upper airway. But we recognized that these drugs have a pretty short duration of action, about 30 to 45 minutes, so we needed to have a way to deliver the medication on more of a continuous basis without obligating a clinician to manually apply it.

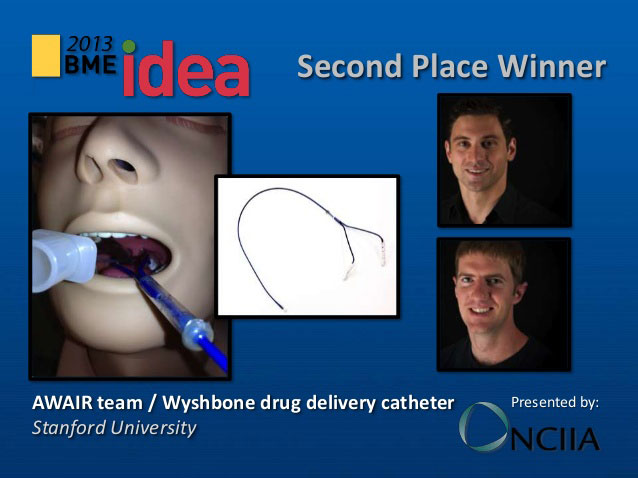

Co-founders Rush Bartlett and Ryan Van Wert.

Co-founders Rush Bartlett and Ryan Van Wert.

The Awair solution is a catheter that slowly drips the lidocaine at select locations in the upper airway to provide an anesthetic effect for intubated patients.

The Awair solution is a catheter that slowly drips the lidocaine at select locations in the upper airway to provide an anesthetic effect for intubated patients.

Our solution is a catheter that slowly drips the lidocaine at just the right spots in the upper airway to provide an anesthetic effect. But it does this in a way that, once placed, the nurse, respiratory therapist, or physician doesn’t have to manage it on an ongoing basis.

At what stage of development is the solution?

Ryan: The device is still in the preclinical stage of development.

Tell us about a major obstacle you encountered and how you overcame it.

Ryan: Convincing people that the endotracheal tube was the driver of the need for sedation was unexpectedly challenging. We were able to identify a handful of key opinion leaders [KOLs] early on who understood the insight and saw the opportunity to reduce the cost and consequences of so heavily sedating ventilated patients. But aside from those KOLs, we were surprised by how many people were comfortable with the status quo and seemed to believe that patients in the ICU were simply so sick that they had to be sedated.

Ultimately, what will change people’s minds is having the right data to demonstrate how a reduction in sedation can lead to associated benefits for ventilated patients. And it important that we continue to identify those KOLs who ‘connect the dots’ and can tell that story on our behalf.

“Convincing people that the endotracheal tube was the driver of the need for sedation was unexpectedly challenging.”

What role did your Biodesign training play in enabling you to design, develop, and/or implement this solution?

Rush: One way that Biodesign was instrumental in this project was in helping us understand that small actions can have big downstream consequences in terms of creating value. By dripping numbing medication in the back of the throat for ventilated patients rather than heavily sedating them, we have the potential to generate billions of dollars of healthcare savings through the avoidance of sedation-related complications.

What advice do you have for other innovators about health technology innovation?

Rush: When you’re looking for unmet needs, don't prejudge your observations before you write them down. It would have been easy for to dismiss my question about what would happen if a bug crawled into the open mouth of the patient who was ventilated in the ICU. But something that started off as somewhat laughable ended up leading to an important unmet need. The only reason that happened was because we were humble enough to write it down. And then we were analytical enough dig into the problem and the value associated with solving it. That opened our eyes to an important opportunity related to the real costs of sedation in the ICU.

Rush Bartlett and Ryan Van Wert launched Awair out of the Biodesign Innovation Fellowship in 2013.

Disclaimer of Endorsement: All references to specific products, companies, or services, including links to external sites, are for educational purposes only and do not constitute or imply an endorsement by the Byers Center for Biodesign or Stanford University.