March 10, 2013 - By Elizabeth Devitt

In the largest study ever to explore new ways to prevent melanoma, researchers at the Stanford University School of Medicine have discovered that women who took aspirin on a regular basis reduced their risk of developing this skin cancer. Results also showed that the longer women took aspirin, the lower their risk.

The study was published online March 11 in the journal Cancer.

The data for the study were drawn from the Women’s Health Initiative, a broad demographic of postmenopausal U.S. women ages 50-79 who volunteered to provide information about their lives — such as diet, activity, sun exposure history and medication — for an average of 12 years to help researchers understand factors that may affect the development of cancer and other diseases.

The Stanford study focused on the data of roughly 60,000 Caucasian women who were selected because less skin pigment is a risk factor for melanoma. The Stanford researchers found that those who took aspirin decreased their risk of developing melanoma by an average of 21 percent. Moreover, the protective effect increased over time: There was an 11 percent risk reduction at one year, a 22 percent risk reduction between one and four years, and as much as a 30 percent risk reduction at five years and beyond.

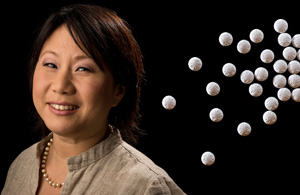

“There’s a lot of excitement about this because aspirin has already been shown to have protective effects on cardiovascular disease and colorectal cancer in women,” said Jean Tang, MD, PhD, an assistant professor of dermatology and senior author of the study. “This is one more piece of the prevention puzzle.”

Stanford medical student Christina Gamba was the lead author of the study. The findings also show that it’s important to invest in long-range studies because so much information can be gleaned from them, Tang said.

The WHI participants provided information at the beginning of the initiative and then at follow-up clinical visits. Researchers verified whether they actually used aspirin or a nonaspirin, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug by having them bring in the bottles of their medication. Based on that information, the participants were divided into three groups: aspirin users, nonaspirin NSAID users and nonusers of NSAIDs/aspirin. Dermatologists evaluated or confirmed the melanomas reported during the initiative.

The findings of the Stanford study are important because aspirin is known to have other protective effects in women, said Tang. So if aspirin can also reduce the risk of melanoma, then it may play a more important role in strategies for preventing other kinds of cancer. The overall incidence of melanoma has been reported to be increasing, with the highest risk in younger women and older men.

One way aspirin may prevent melanomas is through its anti-inflammatory effects, Tang said. Even though non-aspirin NSAIDs also reduce inflammation, they don’t use the same pathways that aspirin uses to become activated in the body. That difference may be the key to aspirin’s effectiveness.

Although the study results are promising, Tang isn’t ready to say an aspirin a day will keep melanomas away. “We don’t know how much aspirin should be taken, or for how long, to be most effective,” she said. There are also downsides to aspirin use: stomach complaints, ulcers and bleeding are all potential side effects. However, she noted that 75 percent of women in the study were taking regular or extra-strength aspirin, not baby aspirin.

These results conflict with previous studies that showed no effect of alternate-day, low-dose aspirin and vitamin E intake on melanoma risk or other cancer incidence. But Tang said the aspirin dose in those studies may have been too low to have any impact.

One drawback of this study was it was based solely on self-reporting. Researchers relied on participants to report actual aspirin intake, sun exposure and other lifestyle choices that could have affected the results. The gold standard is a “proof of concept” clinical trial in which researchers link a specific medication directly to reduced melanoma risk, Tang said.

There also were significantly fewer women taking nonaspirin NSAIDs enrolled in the study, which may have led to the lack of a measurable effect for nonaspirin NSAIDs as a whole. A comparable group with longer-term, nonaspirin NSAID use would have been valuable to assess because other studies have found that NSAIDs can help prevent cancer.

An eight-week trial of the NSAID sulindac, conducted at Stanford, demonstrated its potential as a chemopreventive agent for patients at increased risk for melanoma, noted Susan Swetter, MD, a professor of dermatology and co-author of the paper.

The researchers plan a longer-term clinical trial to determine whether sulindac helps reduce the risk of melanoma among patients with atypical moles on their skin. They then hope to conduct a study to see how that NSAID compares to aspirin in helping to prevent melanoma.

“We and other researchers are trying to identify commonly used and available vitamins, supplements and drugs, such as aspirin and other NSAIDs, that may prevent melanoma,” Swetter said. “Our aim is to find a drug or agent that is readily available, and which will be well-tolerated, safe to use and protective against cancer development.”

Other Stanford co-authors were professor of medicine Marcia Stefanick, PhD, and associate professor of medicine Manisha Desai, PhD.

The work was supported in part by the WHI, which is funded by the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute and the National Institutes of Health (grants N01WH22110, 24152, 32100-2, 32105-6, 32108-9, 32111-13, 32115, 32118-32119, 32122, 42107-26, 42129-32, and 44221). It was also supported by the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases (grant 1K23AR056736-01), a Damon Runyon Clinical Investigator Award and a Selected Professions Fellowship from the American Association of University Women. Information about Stanford’s Department of Dermatology, which also supported the work, is available at http://dermatology.stanford.edu.

About Stanford Medicine

Stanford Medicine is an integrated academic health system comprising the Stanford School of Medicine and adult and pediatric health care delivery systems. Together, they harness the full potential of biomedicine through collaborative research, education and clinical care for patients. For more information, please visit med.stanford.edu.